The issue of inequality has long been debated in both academic and policy circles. It manifests in the everyday functioning of societies and economies and serves as both a cause and a consequence of certain economic, social, and political factors. The first major contribution to understanding inequality in economics was made by Max O. Lorenz (1905), who proposed the Lorenz Curve. This graphical representation illustrates the distribution of income or wealth within a population, showing the cumulative share of income earned by different segments of the population. Building upon this analytical framework, Corrado Gini (1912) introduced the Gini Coefficient, a measure of income or wealth inequality. The Gini coefficient ranges from 0 (perfect equality) to 1 (perfect inequality) and is calculated as the ratio of the area between the Lorenz curve and the line of equality to the total area under the line of equality. However, these measures are time-static and do not elaborate on the trajectory of inequality within or across countries. This limitation was addressed by Simon Kuznets (1955), who hypothesized an inverted U-shaped relationship between economic development and inequality, known as the Kuznets Curve. Kuznets argued that in the early stages of industrialization, inequality increases due to structural changes in the economy, but it decreases as societies mature and wealth is redistributed. While the framework has been debated, it remains foundational in understanding structural changes and inequality.

Economists later argued that relying solely on income as a metric to analyse inequality is insufficient. Amartya Sen, in his influential lecture titled "Equality of What?" (Sen, 1979), critiqued the sole-reliance on income and wealth as only indicators of inequality. Instead, he proposed focusing on capabilities—the freedoms individuals have to achieve well-being. Sen’s Capabilities Approach became the foundation for the Human Development Index (HDI), emphasizing multidimensional aspects of inequality.

Simultaneously, several scholars explored approaches to addressing inequality beyond its measurement. Anthony B. Atkinson (1969) presented a seminal work on the normative approach to inequality measurement, emphasizing social welfare based on utility maximization principles. He proposed the Atkinson Index, which is grounded in the concept of Equally Distributed Equivalent (EDE) Income—the level of income that, if shared equally, would provide the same societal welfare as the observed income distribution. This utilitarian-based framework, however, faced criticism of being too dismissive to understand the distinction between person whilst maximizing aggregate welfare. This was highlighted by John Rawls, in A Theory of Justice (1971), where he introduced the Difference Principle, which argued that inequalities are acceptable only if they benefit the least advantaged members of society. Rawls emphasized primary goods—resources and opportunities necessary for individuals to pursue their life plans—as the basis for evaluating social arrangements. His framework marked a significant departure from utilitarian approaches, focusing on fairness and justice as central to addressing inequality.

As the era of neo-classical economics emerged in the late 1980s, growth-centered liberalization policies dominated the developing world, relegating the issue of inequality to an afterthought in the pursuit of enlarging the “size of the pie”. However, the COVID-19 pandemic, which reversed the era of economic convergence, brought inequality back to the forefront by exacerbating existing disparities and pushing millions into extreme poverty. This renewed focus on inequality spurred studies examining its intersections with various global challenges, including climate change, trade, food security, resource mobilization, financial architecture, and social mobility. These dimensions underscore the multifaceted and deeply entrenched nature of inequality in today's world.

At this critical juncture, Thomas Piketty's seminal work offered a historical perspective on inequality, tracing its evolution from the heyday of Western imperialism in the 1820s to the present day. The World Inequality Report (2022), published by the World Inequality Lab and supported by the World Inequality Database, provides insights into economic inequality trends, their drivers, and implications. The report reveals that global wealth inequalities are even more pronounced than income inequalities. For instance, the poorest 50% of the global population owns just 2% of total wealth, while the richest 10% controls 76%. Similarly, the wealthiest 10% of individuals receive 52% of global income, whereas the poorest half earns only 8.5%.

These disparities have intensified since the 1980s, driven by financial deregulation and market liberalization policies that took varied forms across countries. The report also highlighted inequalities in health and education, showing that inequality is not confined to wealth and income but extends to broader aspects of human development. To address these challenges, Piketty proposed several redistributive measures, including taxing ultra-high-net-worth individuals to fund essential public goods and services such as healthcare and education.

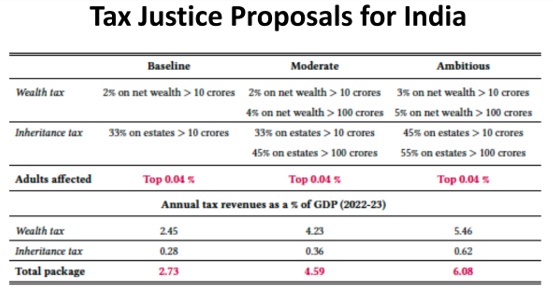

During a recent conference in New Delhi in December 2024, Piketty introduced a Tax Justice Proposal for India (see Fig. 1), further advancing the discourse on actionable solutions to tackle inequality in one of the world’s most diverse and populous economies.

Source: Thomas Piketty (2024) – Conference Presentation: Inequality, Economic Growth and Inclusion. New Delhi.

The idea of a global wealth tax or inheritance tax has been a focal point of discussions in policy circles worldwide, particularly within multilateral platforms like the G20. Under Brazil's current G20 presidency, addressing inequality has been identified as a key priority. In line with this, a report titled A Blueprint for a Coordinated Minimum Effective Taxation Standard for Ultra-High-Net-Worth Individuals was proposed. The baseline recommendation suggested that individuals with wealth exceeding $1 billion should pay an annual minimum tax equivalent to 2% of their wealth.

While this proposal garnered significant support from academics and policymakers, it failed to reach a conclusive agreement as the G20 Leaders’ Summit in Rio de Janeiro concluded without a consensus on global wealth tax. The declaration only states that “With full respect to tax sovereignty, we will seek to engage cooperatively to ensure that ultra-high-net-worth individuals are effectively taxed”.

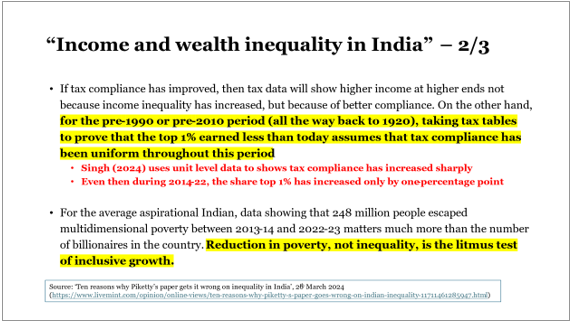

In India, the debate around taxing the wealthy has been met with caution. Chief Economic Advisor V. Anantha Nageswaran has warned that such measures could dampen economic growth and trigger capital outflows—an example of the "law of unintended consequences." He also highlighted methodological concerns with Thomas Piketty’s inequality metrics, emphasizing that for a developing country like India, the true measure of inclusive growth lies in poverty alleviation rather than solely addressing inequality (Fig 2). This underscores the complexity of implementing redistributive policies in a way that balances equity with economic stability.

Source: V. A. Nageshwaran (2024) - Conference Presentation: Inequality, Economic Growth and Inclusion. New Delhi.

In conclusion, inequality has been a defining marker of civilizations and regimes throughout history, manifesting in the daily lives of individuals. Inequality has persisted across eras, shaping the functioning of societies and economies, though its degree varies—some societies are significantly unequal, while others are relatively less so. The processes of wealth accumulation, extraction, and redistribution have historically paved the way for phenomena like colonization and decolonization.

Therefore, addressing such an intricate issue like inequality in today’s world is a complex challenge. On the one hand, there is an urgent need to fund social infrastructure and public goods such as healthcare and education to invest in human development and lift people out of multidimensional poverty, which often require robust redistributive policies. On the other hand, taxing the ultra-wealthy in an era of excessive financialization and unrestricted capital mobility creates a classic game-theory dilemma: the more countries that commit to a global tax mechanism, the greater the incentive for a single nation to opt out and attract capital flight. This conundrum underscores the difficulty of balancing equity with economic pragmatism in a globalized world.

The article is based on a panel discussion organised by Research and Information Systems for Developing Countries (RIS) in collaboration with Delhi School of Economics. The panellists ofthe discussion included Professor Thomas Piketty, Paris School of Economics; Dr. Shamika Ravi, member of the Economic Advisory Council to the Prime Minister; Dr. V. Anantha Nageshwaran, the Chief Economic Advisor to the Government of India; Dr. Ravindra H. Dholakia, member of the RBI Central Board; Professor Sachin Chaturvedi, Director General RIS and Professor Ram Singh, Director of Delhi School of Economics.

For more information on the panel discussion, visit: https://www.ris.org.in/node/3993

*Syed Arsalan Ali is Research Assistant at RIS. Views expressed are personal. Usual disclaimer applies.

Author can be reached out at syed.ali@ris.org.in