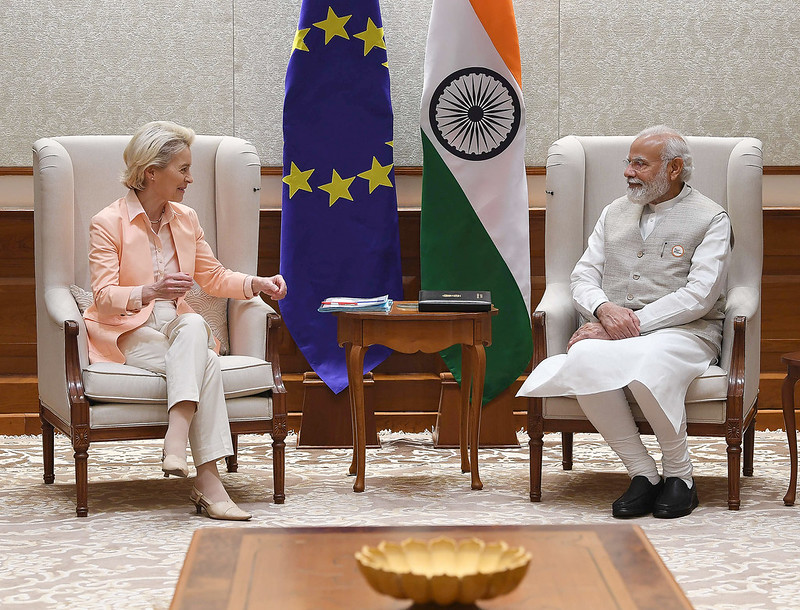

During the visit of European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen with the European Union (EU) College of Commissioners in February 2025 to India, the leaders of the two countries committed to pursue negotiations for a balanced, ambitious, and mutually beneficial Free Trade Agreement (FTA) with the aim of concluding them within the course of the year. The talks are moving in a positive direction even though not much has been heard after the signals about an early harvest by July.

In the current geo-economic cauldron, India and the EU are more likely to move forward towards a significantly beneficial trade deal than several other permutations and combinations criss-crossing the global bilateral trade agenda of India. India and EU have been in a Strategic partnership since 2004. Negotiations on a broad-based Bilateral Trade and Investment Agreement (BTIA) began in 2007 but were stalled in 2013, and resumed only in 2021.

Going by the reasons behind the earlier hiatus, the differences in the respective goals of India and the EU were quite wide. EU had a large agenda on Intellectual Property Rights (IPRs), investment protection, massive import duty cuts and sustainable development related goals. India, on the other hand, wanted a more liberal visa regime for skilled professionals, addressing non-tariff measures, and keeping government procurement out. Understandably, the resumed negotiations aim at three separate agreements, two of them on investment protection and geographical indications, making it possible to try for an early harvest on trade. Contentious issues like data privacy and security related legislation, Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), IPRs, and competition can wait. Opening up Government procurement could be considered on the lines of the deals India has crafted with UAE and UK recently, thus protecting the MSMEs of India.

In a challenging regional and international environment, the EU and India share the values of democracy, human rights, fundamental freedoms and support the rules-based global order centred on multilateralism. Both represent ‘unions of diversity’ and have important stakes in each other’s prosperity and sustainable development. The EU strategy and roadmap for India propose, inter alia, to build a strong partnership with India for sustainable modernisation, join forces with India to consolidate the rules-based global order, based on multilateralism with the United Nations (UN) and the WTO at its core, and develop a shared approach at the multilateral level to address global challenges. Hence, both India and the EU stand to benefit from closer cooperation in trade, investment and technology related matters. With the current EU roadmap for India ending this year, it is the right time for India to engage with the EU to get its interests accommodated in the next roadmap.

So, where do the two markets stand today? At present, trade between India and EU is conducted based on the WTO Most-Favoured Nation status. India-EU bilateral merchandise trade grew from Euro 4.4 billion in 1980 to Euro 40 billion in 2005, and to Euro 132 billion in 2024. India’s merchandise exports primarily comprise of manufactured goods including machinery and vehicles, and chemicals, while imports were also of manufactured goods and chemicals. The weighted average tariff of EU is 2.7%, while that of India is 12%. There will be expectation from the EU for India to reduce tariffs. For balance, India must focus on seeking conversion of some of the specific duties imposed by EU into ad valorem duties. India may also consider seeking resumption of standard GSP preferences from EU, without agreeing to the conditions imposed for GSP+ preferential treatment and restraining organic evolution of India’s policies on environment and labour standards.

Low tariffs in EU hide the fact that the elephant in the room for prising open the EU market is their non-tariff measures (NTMs). These include measures for circularity and energy efficiency, carbon footprint, waste management, water management, and sustainable forestry, to list a few. Traditional non-trade barriers that impacted Indian exports adversely ranged from reduced minimum residue levels (MRL) for a fungicide used in rice cultivation in 2017 that impacted rice exports, and the stringent regulations under the Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals (REACH) programme, implemented in 2007 that impacted chemicals exports. Indian merchandise exporters also have significant concerns relating to governmental regulations, customs procedure and licensing, technical standards and health regulations, sanitary and phytosanitary measures, and certification as the major barriers to export. It is important to negotiate the development of mutual recognition of the assessment activities of compliance (like in the EU-Vietnam FTA), and an agreement to accept each other’s conformity assessment procedures (like in the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement between the EU and Canada). The possibility of having EU carve out a separate channel for testing Indian exports through India based testing agencies may be considered so that cost of compliance can be manageable.

Another prominent non-tariff measure India faces in the European Union is the safeguard duties on steel, which were first imposed in 2018 and then extended this year till 2026. EU is an important export market for Indian steel, particularly after the uncertainty arising in the exports to the US due to the tariffs imposed by the US. Rules of Origin (RoOs) is another NTM that needs to be addressed through negotiations to prevent circumvention when exporting through the preferential tariffs window, like for GSP. It may be useful to develop product specific RoOs for goods like fish, textiles, and some agricultural products. Even the European Textile industry seeks product specific RoOs.

To these have been added several recent sustainability related barriers such as the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) and Deforestation-free Regulation (EUDR) that will impose taxes on imports based on carbon emission intensity. While both sides have discussed the challenges arising out of CBAM implementation, in particular for the small and medium enterprises, they have agreed to continue addressing them without any logical conclusion yet.

Let us move to services from merchandise. India-EU bilateral services trade is about Euro 51 billion. India’s exports mainly comprise of business services, transport services, IPRs, ICT services, and travel services, while imports also comprise mainly of business services, transport services, ICT services, travel services, and IPRs. The EU service market is very heterogeneous in regulations and conditions for the third countries – exporters of services. A deal in services trade could be mutually beneficial. According to a recent UNESCAP study, India has comparative advantage in professional and management services in 25 EU countries. There is considerable scope for mutually beneficial increase of services trade between India and the EU provided the domestic regulations of services from each other is facilitated. Given the difficulties faced and time taken in signing mutual recognition agreements, specific understanding may need to be reached to include disciplines on specific professional services. Also, specific disciples may be negotiated drawing on WTO accountancy sector disciplines, the WPDR frozen text under Article VI:4 of GATS, and the approach used in the India-EFTA free trade agreement.

Investment, technology, and IPRs are the other major issues. The investment chapter may have to be delinked from the trade early harvest if a deal is to be made this year, as India is reviewing its model Bilateral Investment Treaty (BIT). However, it is noteworthy that the EU is a significant source of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) for India, with total FDI estimated at USD 117.34 billion. While the evolution of a revised model BIT may take time, the possibility of having investment promotion and cooperation related provisions in the India-EU FTA may need to be considered. The provisions agreed in the Trade and Economic partnership Agreement (TEPA) between India and the European Free Trade Association (EFTA) may be of relevance in this regard. An investment chapter along with the constitution of a committee on investment promotion and cooperation could be considered. Chapter 7 on investment promotion in the TEPA explicitly rules out recourse to the more elaborate dispute settlement provisions that apply to the rest of the provisions of TEPA, but a consultation mechanism and provisions for remedial measures are provided for in the event that the EFTA States do not meet their obligations to promote FDI into India.

The big takeaway from the recent reinvigoration of India-EU trade talks is the promise of cooperation in the technology sector. The EU-India Trade and Technology Council (TTC), launched in 2023, is only EU’s second after that with USA. It’s three working groups covering strategic technologies, resilient supply chains and clean and green technology aim to bring together high-level representatives and experts from both sides. India can benefit from clean and green technologies developed in the EU, as has happened in the past as well. Cooperation would be mutually beneficial in areas such as policy and regulatory frameworks, identifying cutting-edge green technologies, pinpointing collaboration opportunities and gaps, fostering co-development of technologies, and establishing institutional collaboration initiatives.

The issue of intellectual property protection can be contentious between the two trading partners, particularly because of the ongoing concerns of the EU on Indian patent protection system and, in particular, Section 3 (d) of the Indian Patents Act that prevents evergreening of patents through incremental inventions that do not add to known efficacy of products or processes subject of a patent. India has a robust set of national IP laws which are fully compliant with its obligations under the TRIPS Agreement of the WTO. EU has been collaborating with India in improving the patent examination system in India through capacity building of patent offices. European Patent Office (EPO) and Intellectual Property Office of India (IPOI) have an ongoing bilateral cooperation framework for the purpose. Similarly, the project EU-India Intellectual Property Cooperation (IPC-EUI) has been undertaking capacity building for trademarks office in India. Now these engagements can be raised to a higher level with TTC.

*Atul Kaushik is GDC Fellow at RIS. Views expressed are personal. Usual disclaimer applies.

Author can be reached out at atul.kaushik@gdcin.org